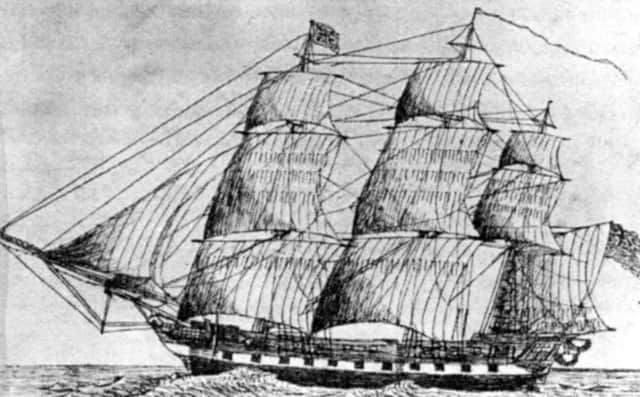

South Shields ancestor's sailing ship days

It is the tale of the wooden sailing ship, Hindostan (renamed HMS Buffalo) which sailed for 17 years before ending its days at the bottom of the sea off the East coast of the North Island of New Zealand in 1840.

The story is told by Dorothy Ramser, the youngest daughter of the founder of MI Dickson.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdShe says: “Ships just like this were built on the Tyne by our craftsmen, and the region provided men to sail them to far distant corners of the world at a time when Britain dominated the high seas.”

Hindostan’s story begins in the shipyard of Bonner & Horsburgh in India.

“James Bonner, my paternal ancestor, was born in Berwickshire in 1770.

“He travelled to Bengal in 1793 under the profession of blacksmith – a career closely linked to shipbuilding.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Once there, he quickly opened a flourishing boat building and shipbuilding business in Sulkea.

“He also owned a large blacksmith’s business on Clive Street, in Calcutta.

“He stayed in the Calcutta area for 20 years, an unusually long period of time for a European to survive in the crushing climate of Bengal.”

Dorothy reveals that life expectancy for most westerners was around two years, before they succumbed to one of the many diseases rife in the swampy, mosquito-infested region.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“This would indicate that Bonner had adopted Indian customs in his daily habits, like wearing light, loose fitting Indian clothes and eating sparse amounts during the heat of the day.

“To communicate, he would have been obliged to have a working knowledge of Urdu and Hindu, or even Persian.

“These skills were usually learned via a tutor before leaving for India, or en route with a type of teach-yourself book.”

She said a civilian had to get permission from the East India Company in order to travel to one of its territories.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs well as paying for a costly sea voyage, they also had to pay a bond to the company which ranged in sum from £300-£700 plus.

But fortunes were to be made in India and it was no doubt worth the risk and expenditure.

“Bonner & Horsburgh had a partnership that built two ships (as far as is known), the Severn, in 1812, and Hindostan in 1813.

“Both teak ships were sheathed in copper, an innovation for protecting the timber from sea worms, and which also vastly increased the speed of the vessel at that time.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTogether, they sailed with the fleet to London on a voyage that Dorothy now documents.

“At this time, in the early 19th century, the amenities provided in the average cabin on board ships were spartan, to say the least.

“A swinging cot was pvided which had to be strung up between the beams during the day to give more space in the cabin.

It was advisable that the cot was provided with rails to prevent the occupant rolling out and being badly injured as the ship heaved and rolled.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Cabins were generally constructed of wooden partitions, but had a door with a lock.

“During wartime, partitions were made of canvas and fixed to the beams above, which were rolled up whenever the vessel had to be cleared for action.

“Some cabins included a porthole – the gun for it was sent forward, and lashed up to the ship’s side, the muzzle pointing forward; but if there was an emergency, the cabin was knocked down, hopefully after alerting the relaxing seasick passenger in his swinging cot, and the gun immediately positioned and ready to fire.

“Comfort does not seem to have been a priority, and passengers were expected to fight with side-arms and cutlass if the ship was attacked. Each Sunday, the captain led the practice drill to fire the guns.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It puts a whole new perspective on the cruise experience...”

Dorothy explains that, as a guide, it cost approximately £200-£300 for a berth with a window.

Services on board were provided by two or three men at a cost of about three or four guineas, and their role was to clean boots and shoes, brush clothes, clean the basins and provide hot and cold water.

“Breakfast was generally eaten at eight, dinner at two, tea at six, and supper at nine.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Breakfast would normally consist of tea and coffee, with biscuits and, at times, rolls.

“The butter resembled liquid honey as it was impossible to stop it melting.

“As much fresh meat as possible was taken on board at the time of sailing – some joints of good beef and mutton would be served up for the first week, after which corned meat came into use.

“There would have been an ample supply of poultry, of all descriptions, fed in coops on the poop, and a small flock of sheep, maintained there on hay, which would enable the captain to provide fresh meat of some sort every day.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“This, as well as an abundance of salted beef and pork, together with tongues, pickles, sauces of all kinds, potatoes, rice, pastry, olives etc, made sure passengers did not go hungry.

“ Supper consisted chiefly of cheese and biscuits and what is called rasped beef and sago soup.”

Wine was also provided, hardly surprising when you hear what one writer at the time said about it.

“The water taken on board, being strongly impregnated with filth of various kinds and colours, soon becomes too nauseous for the use of delicate persons. I think most people would have preferred to stick to alcohol – the habitual beverage was table beer or port.”

• Dorothy concludes her story tomorrow.